EV Charging: The New Gold Rush

Simon Fraser University’s experience implementing a new parking revenue stream.

By David Agosti

Simon Fraser University’s (SFU) main campus is located in Burnaby BC. SFU has over 5,000 parking spaces and EV Chargers has been part of their parking supply since 2012. Starting in 2021 (post-COVID) SFU has been expanding their EV Charging network in order to provide a service to customers, assist governments in their EV Charging goals, and provide an additional revenue source to the University.

Some EV Charging Basics

As the world of EV Charging evolves it is helpful to understand some of the basic terminology:

- Port – the part of the EV Charger that supplies power to the electric vehicle via a cable and charging head. Some EV Chargers have one port (can charge 1 car), and some have two.

- Level 1 Charger – slowest form of charging utilizing a 110V outlet. Normally to use a Level 1 charger the driver needs their own cable and charging head that was supplied with the car.

- Level 2 Charger – a mid-speed form of charging using AC power varying from 7KWH to 19KWH depending on model. Most Level 2 chargers have 2 ports.

- DCFC (Level 3) Charger – the fastest form of charging using DC power varying from 50KWH – 350KWH depending on model. DCFC’s fill an EV batter to approx. 90% charge after which they provide a trickle charge so as not to damage the battery.

- KWH – Kilowatt-Hour – EV Charger speeds as well as EV battery capacity are measured in KWH.

- LCFS – Low Carbon Fuel Standard – in BC (and some US States) a program that aims to reduce the carbon intensity of transportation fuels. Clean fuel providers can earn credits and then sell those credits to suppliers of higher carbon intensity fuels.

- CFR – Canadian Clean Fuel Regulation Program – energy supplied via EV Chargers can generate a clean fuel credit (depending on how “clean” the energy supply is) which is then traded on the Canadian Federal Clean Fuel Regulation carbon market.

- OCPP – Open Charge Point Protocol – a shared “language” between EV Chargers and charging station management systems software. Not all EV Chargers subscribe to this protocol, and of those that subscribe not all subscribe to all components.

- Overstay – term used for EVs that remain parked at an EV Charger after they have finished charging.

The standards and nomenclature are changing and often need clarification. For example: sometimes “ports” and “chargers” are used interchangeably, but they are not the same thing (SFU has twice the number of ports as chargers – because SFU’s chargers are dual-port). Various locations can each have a DCFC install, but the speed of charging can vary greatly based on the DCFC’s power rating.

The SFU Experience

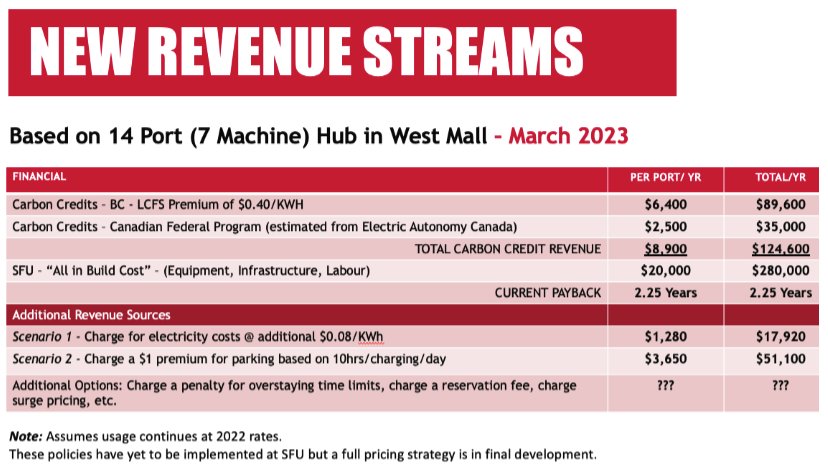

SFU is pursuing a public mixed-use EV Charging concept with the goal of 74 ports by the end of 2024 and 174 ports by 2030. The implementation involves multiple 14 port “Charging Hubs” across campus fulfilling a three-part concept of infrastructure, public usage, and revenue generation.

Analysis of SFU’s electrical infrastructure indicates that 14 ports maximize efficiency and reduces the cost of the necessary infrastructure. Less and there would be “room left” on the electrical supply in various locations, more would require adding additional infrastructure (e.g., transformers). The all-in cost of such a hub approaches $300,000. This includes everything: wiring and transformers, EV Chargers, warranty and software, paint, and signage, etc. but does not include any potential subsidies (government subsidies for installation vary over time and jurisdiction).

Universities are a “City-within-a-City”. In the case of SFU, there is the University as a workplace with 14,000 vehicle trips per day and a campus population of 32,000. There is the University as a residence with 10,000 Residents on or near campus in Student Residences or adjacent market-based apartments. There is the University as a retailer with dining facilities serving 10,000 meals a day and a commercial High Street with grocery stores and restaurants. Finally, the University as a destination for the general public: the pool/gym acts as a Community Centre and events are regularly held on campus.

Figure 1 illustrates how one of SFU’s EV Charging Hubs is located to take advantage of this mixed use:

By placing an EV Charging Hub in proximity to all these uses, SFU maximizes the use of the infrastructure and the “flow of electrons” per day. In the above example faculty/staff/students use the EV Chargers during the day, people eating at restaurants and grocery shopping use it during evenings and weekends, and residents of the apartment buildings charge their vehicles overnight (since their buildings are not retrofitted with EV Chargers). SFU fleets only charge off-peak (parking enforcement vehicles are EVs) allowing the public to use that infrastructure during the day.

Parking analytics indicate that average length-of-stay at SFU parking facilities is 3-4 hours. This length-of-stay combined with Level 2 Chargers provides the charging time users need. Using a Tesla Model 3 as an example, it has a 60KWH battery (80 KWH in the extended range model). If parked for 3-4hrs at a 7KWH Lvl2 charger, this would replenish 50% of the vehicles charge during that time. A 19KWH Level 2 charger would fully charge the Tesla.

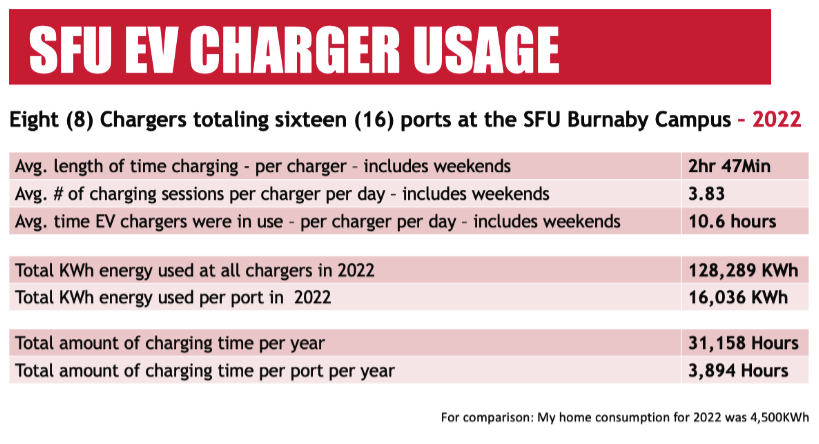

Combining charge time with the barrier-free nature of public mixed use charging means the SFU model has 4 EVs charging per day at each port, for an average of 10.5 hours of charge time, utilizing 16,000KWH of energy per year per port as shown below (note SFU was able to install 16 ports at this location).

In the parking industry we utilize a KPI of revenue-per-stall, and over time we have realized that transient parking maximizes this KPI beyond monthly permit parking. The same is true of EV Charging. The reason SFU does not restrict EV Charging to our direct community, or to SFU fleets only, is to maximize

the “flow of electrons,” maximize turnover, and thereby maximize revenue.

Being located in BC, SFU has the benefit of the BC LCFS and the ability to claim and sell carbon credits. This increases SFU’s revenue and shortens the payback time on investment. However, even without carbon credits EV charging represents a worthwhile revenue stream. SFU is still deciding on whether to: charge for electricity or charge a parking premium (e.g., regular space $5/hour, EV space $6/hr), and/or charge a reservation fee, and/or charge a penalty for overstay, etc. In addition, all jurisdictions in Canada will qualify for the federal CFR program. A revenue example from SFU’s most recent EV Charging Hub implementation is detailed below:

The above revenue numbers are only possible because of the mixed-use EV Charging strategy. SFU has been told their average of 10.5 hrs/day “flowing electrons” is the highest in Canada. If SFU restricted their charging to workplace only it would likely average 3 hrs/day, 72% less usage meaning 72% less revenue.

A further example: the average Canadian drives 15,200KM/year or 300KM/week. Once again using a Tesla Model 3 as an example, the Tesla uses 15KWH / 100KM travelled, meaning for the 300KM/week the average Canadian drives, the Tesla would need 45KWH of charging per week. This works out to 6.5hrs of charging per week at a Level 2 Charger.

SFU’s 10.5hrs/day (74hrs/week) of mixed-use EV Charging provides enough charging at each port for the weekly needs of 11 EV drivers. At SFU’s 2030 roll-out of 174 ports that represents almost 2,000 EV drivers who are getting all the charging they need from SFU’s infrastructure. These numbers are what drive the revenue.

Future Challenges and Opportunities

Carbon Credit revenues will not last forever. SFU’s consultants expect the revenue from the BC LCFS to drop by 75% by 2030. However, the EV Chargers SFU installed in 2012 are still functional and SFU believes that the additional revenue sources listed above will continue to provide a viable revenue stream into the future.

Less well known is the impact of developing consumer behaviour in how drivers will charge their EVs. EV Charging is neither a gas station solution nor a parking solution – but something in between. Utilizing the fastest DCFC charging, it still takes 5X – 10X as long to “fill” an EV as it does to fill a gasoline powered vehicle. Some providers are pursuing a gas station model whereby the driver sits in their car or sits in a lounge while their EV chargers – essentially, they are single-tasking. SFU does not believe this is the future. Rather the future is one of parking the EV while it charges and multi-tasking: working, shopping, eating, going to the gym – all while the EV Charges. Consumers have yet to dictate their preference, so it is up to parking & EV Charging providers to lead the way.

The second consumer behaviour challenge is one that the parking industry is familiar with – creating a barrier-free environment for payment, validation, and data collection. As much as the OCPP standard exists in the EV Charging world, it is nowhere near as seamless as the systems the parking industry has developed for mobile payment, QR code systems, gate activation systems, etc. EV Charging still requires a variety of apps or systems to pay for parking, activate the EV Charger, and pay for the EV Charging. The same is true on the back end: a variety of systems for tracking usage, scope 3 emissions reduction, and LCFS/carbon credit reporting. There is a huger opportunity for parking systems and software providers to solve these problems, reduce barriers, and create efficiencies in this space.

After the success of multiple EV Charing Hub installations on campus, SFU is now developing a Mixed-Use EV Charging Action Lab in conjunction with other partners to assist Governments, NGOs, and other public and private organizations in meeting their 2030 and 2040 EV Charging goals. For further information, feel free to contact the author.

About the author:

David Agosti, Director – Parking & Sustainable Mobility Services, Simon Fraser University

daagosti@sfu.ca