Data is the Key to Modernizing Curbside Management

By Adam Wenneman

The curbside is one of the most poorly understood parts of the municipal right-of-way. On the one hand, it’s a huge piece of municipal infrastructure that is essential to the urban transportation landscape, supporting billion-dollar industries like goods movement and ride sharing. On the other, it is a scarce – and diminishing – resource whose management principles remain rooted in 20th century technologies.

In a time where curbside uses are growing to include expanded patios, dedicated courier loading zones, and other temporary uses, cities need to leverage innovations in collecting, managing, and sharing curb data to improve the efficiency of operations at the curbside.

The Curbside is a Critical Municipal Asset

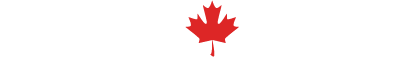

The curbside is a major piece of infrastructure for every municipality. Across Canada, on-street parking represents upwards of 20% of a city’s total parking supply1. In some cities, like Saskatoon or St John’s, on-street parking constitutes almost all of the downtown parking supply. In downtown Hamilton alone, there is room for over 1,100 parking spaces at the curbside – that’s an area equivalent to the size of ten NHL-sized ice rinks. Efficient operation of this space is an important factor in a city’s ability to support the future of urban mobility.

Despite its considerable supply, the curbside remains a limited and scarce resource at a time where demand for curb space is at an all-time high. The curbside is a limited resource in that its supply cannot grow substantially in urban areas with well-defined built environments and road networks. At the same time, cities are beginning to repurpose the curbside and even entire roadways for alternative uses like active transportation, outdoor dining, and shared community space2. Make no mistake – increasing the amount of green, livable space in a city can have major benefits for residents – but that said, further reduction of the supply of curb space means cities need to do even better in effectively managing what space remains.

For its considerable use of curbside space, many Canadian municipalities rely on paid on-street parking as a major revenue stream. On-street parking is revenue positive in nearly every municipality where on-street parking is paid, and the average Canadian municipality can expect to generate an average of $2 for each $1 invested in parking operations3. In addition to funding the operation and maintenance of parking management departments, this revenue flows back into municipal governments and supports all of the other services that local municipalities provide.

Beyond just paid parking, the curbside is also an important access point for the goods movement industry. The curbside constitutes the last link in the ‘last mile’ for deliveries in urban areas, connecting raw materials to the end consumers of goods and services. Given the strong ties between increasing density, population and employment growth, and the growth of commercial vehicle delivery, ensuring that delivery vehicles can access the curbside effectively will be a major factor in determining a city’s long-term sustainability. Despite the function they provide being critical to the liveability of cities, commercial vehicles and the goods movement industry face significant challenges operating at the curb. In Toronto alone, commercial vehicles are issued nearly $30M in parking fines each year4. Given the low-margin, cost-competitive nature of the goods movement industry, the burden of these costs is mostly passed to consumers, resulting in higher prices for goods and services and an increase in the cost of living. If commercial vehicles in the future are unable to operate efficiently in urban areas, cities as we experience them today may no longer exist.

The Curbside is Changing

Despite its important role in supporting urban mobility and the economy, curbside management practices have remained largely unchanged since the installation of the first parking meter in Oklahoma in 19355.

Since 1935, uses of the curbside expanded to a comfortably uniform standard: paid parking for high-turnover streets, free parking in less busy areas, and the occasional taxi stand or delivery zone where demand dictated. Managing these uses was relatively simple and space was plentiful, so there was no need for more than the simplest of management systems here. This pattern of curbside uses continued well into the 21st century, but technological innovations in the past decade have caused tremendous growth in both the demand for space among existing users, and the number of new and unique uses for the curbside.

Today, transportation network companies (TNCs) such as Uber and Lyft together complete more than 15 million daily rideshare trips globally – picking up and dropping off passengers anywhere on the curbside that they can find a spot due to the scarcity of passenger loading zones6. At the same time, delivery vehicles have overwhelmed unpaid commercial loading and no parking zones alike as they rush to meet the ever-growing demand for at-the-door delivery service.

These trends have only been accelerated in 2020 by the impacts of COVID-19. The allocation of curb space has expanded to include loading zones for curbside pickup, wider sidewalks to support social distancing, and patios on sidewalks or on on-street parking spaces. When more than the curbside needed changing, entire streets were repurposed to encourage active transportation while supporting social distancing measures. Almost overnight, huge portions of the curbside were transformed from places to park, stop, or stand to places to sit, walk,

and eat.

These new and growing uses for the curbside have caused the demand for curb space to exceed its supply, resulting in inefficient use as users compete for limited space with limited information. Commercial vehicles park illegally and accept fines instead of spending time searching for loading zones, passenger vehicles cruise endlessly for parking, and the ever-growing list of alternative users for curb space fight for what little space remains.

For every user of the curbside, accessing and understanding information about how and where they can access the curbside is the primary roadblock to using curb space effectively. To better prepare for the future, cities need to be able to communicate curbside regulations to users as quickly as uses and designations of space change.

Data to Enable Modern Municipal Curbside Management

In understanding the issues facing the modern curbside, one question becomes apparent: in the face of growing demand for space and limited supply, how can municipalities manage curbside operations to improve efficiency? The answer to this question comes down to information and making that information accessible to users. Today, curbside regulations are only presented via on-street signage that is frequently difficult to understand, sometimes obscured or damaged, and only available once a user has arrived at the curb. If we could provide this information to users at an earlier point in their journey, we could eliminate cruising for parking, help commercial vehicles quickly find dedicated loading spaces, and make more efficient use of limited

curbside space.

The first step a municipality should take down this path is to digitize their existing curb regulations to form a digital ‘curb layer’. Simply put, a curb layer is a machine-readable, geospatially referenced dataset that can be used to understand the relationships between curbside regulations. A curb layer consolidates information already provided in generally inaccessible formats such as municipal bylaws, signage inventories, and regulation orders, into a consistent and structured format that can be made accessible to users when and where they need it most.

The process of creating a curb layer is simple, with a range of solutions that can be tailored to meet the needs of municipalities of all sizes. These solutions start with simple open source tools, like the SharedStreets CurbWheel. CurbWheel uses a typical measuring wheel, a simple single-board computer for processing, and a smartphone for taking pictures of street signs. There are step-by-step instructions to get started building the tool and collecting data with minimal effort. Using CurbWheel, we estimate municipalities can create a curb layer of existing regulations for small areas with costs as low as $25 per curb kilometre.

For larger areas where walking a curb would be too time consuming or expensive, IBI Group has developed software solutions that build on existing assets to consolidate curbside regulations into a curb layer automatically7,8. These solutions vary in complexity, from cleaning existing data sets to collecting street sign imagery and applying machine learning categorization methods but can help cities create complete and accurate curb layers no matter what existing curb regulation data they have.

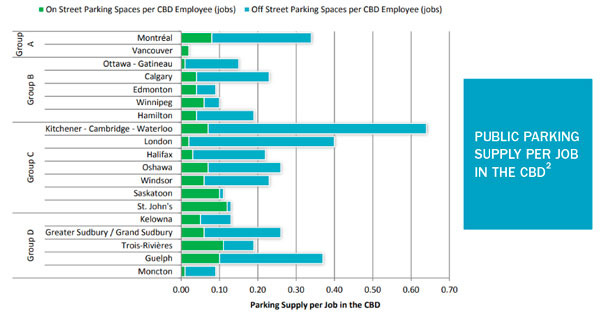

Once this data is collected, municipalities can take advantage of curb management tools like CurbIQ’s Curb Viewer or Curb Manager to help them understand, manage, and analyze this data.8 These tools go beyond existing Geographic Information System (GIS) tools and help staff manage even the most complex situations where many regulations overlap, or change at regular or irregular intervals. These tools can leverage a curb layer to quickly answer fundamental curbside management questions like ‘‘how do the regulations change on this block throughout the day?”, ‘‘do our no parking restrictions make sense?”, or even “if we added a bike lane here, how many parking spaces would we have within walking distance of a given location?”. One city using Curb Viewer was able to identify conflicts between, and gaps within, their existing regulations that they didn’t even know existed and would not have been able to identify with their old workflows.

Everyone Benefits from Proactive and Modern Curbside Management

Beyond improving their own understanding of curbside regulations and improving their workflows for how regulations are managed, cities can also adopt modern solutions to share this data with curbside users to both improve operations and potentially generate new

revenue streams.

As Donald Shoup infamously estimated, as much as 30% of traffic in dense urban areas is made up of vehicles cruising for parking9. What if instead of cruising for parking, drivers could access information on the location of on-street parking near their destination, which is often available just around the corner or a short walk away? Giving drivers access to this information at the navigation or trip planning stages of their trip can have a

meaningful impact in reducing VKT and emissions associated with cruising for parking, resulting in less traffic and greener cities.

The group with potentially the most to gain from improved access to curb data is commercial curbside users – comprised primarily of TNCs and couriers. These are two of the fastest growing users of curb space, but they pay little to nothing for that use in most cases. However, the lack of curb space allocated for these uses causes enormous user costs in the form of parking fines, time spent searching for available spaces, and managing customer complaints caused by delays. Instead, cities could establish programs that provide access to data on the location and/or availability of curbside space in exchange for a small fee paid on a per-trip basis. Such a system would convert costs already being paid by these users to deal with inefficient curbsides new revenue streams for cities while improving the efficiency of curbside operations for everyone.

Preparing for an Uncertain Future

The curbside is a corner piece in the transportation puzzle, facilitating a wide range of uses by a growing number of users. However, accelerating growth in demand for curbside space and limited access to information has led to inefficient curbside operations.

If cities don’t adapt, curbside operations will become increasingly challenging and negatively impact the livability and affordability of urban areas. But if they prepare themselves and harness solutions like digital curb layers and the new types of curb management practices that they enable, cities can adapt to the future of the curbside as quickly as it arrives.

References

1: Kriger, D., Rose, A., Baydar, E., Moore, J., Frank, L., Chapman, J., & Pisarski, A. (2015). Urban Transportation Indicators Fifth Survey. Ottawa: Transportation Association of Canada.

2: City of Toronto. (2020, November 27). COVID-19: ActiveTO. Retrieved from City of Toronto: https://www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-protect-yourself-others/covid-19-reduce-virus-spread/covid-19-activeto/

3: Municipal Benchmarking Network Canada. (2018). 2018 MBNCanada Performance Measurement Report. Retrieved from http://mbncanada.ca/app/uploads/2019/11/2018-Parking.pdf

4: Wenneman, A. (2014). Commercial Vehicle Operations in Urban Areas: Identifying Policies to Reduce Negative Impacts. Toronto: University of Toronto Department of Civil engineering.

5: Coin-In-Slot Parking Meter Brings Revenue to City. (1935, October). Popular Mechanics, p. 519. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?id=wN8DAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA519&dq=Popular+Science+1935+plane+%22Popular+Mechanics%22&hl=en&ei=aJgvTv3XKdSgsQLVyIRv&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&sqi=2&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=true

6: MarketsandMarkets. (2019). Ride Sharing Market by Type, Car Sharing, Service, Micro-Mobility, Vehicle Type, and Region – Global Forecast to 2025. Retrieved from MarketsandMarkets: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/mobility-on-demand-market-198699113.html#:~:text=The%20ride%20sharing%20market%20is,and%20fall%20in%20car%20ownership.

7: IBI Group. (2020). CurbIQ by IBI Group. Retrieved from IBI Group: https://www.ibigroup.com/ibi-products/curbiq/

8: IBI Group. (2020). CurbIQ – Understand, manage, and optimize your curbside. Retrieved from CurbIQ: https://curbiq.io/

9: Shoup, D. C. (2006). Cruising for parking. Los Angeles: Department of Urban Planning, University of California.